- This event has passed.

Images of the World and the Inscription of War

January 20, 2016 @ 7:00 pm– 9:00 pm EST

January 20th, 2016

7pm

@ Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center (map)

$8 General | $6 Students/Seniors | Free for Members of Squeaky Wheel and/or Hallwalls

Once described as Germany’s “best-known unknown filmmaker,” Harun Farocki’s films, installations, and work as a theoretician established him as one of the most commanding observers of modern life. Inspecting the tools and politics of image-making as they marked the 20th and ongoing 21st century, the intellectual framework with which Farocki approached his subjects – surveillance, labor, war, among others – was astonishing for its breadth, acuity, and prescience.

His passing in the summer of 2014 meant the loss of a vital figure in contemporary art and cinema. Squeaky Wheel and Hallwalls Contemporary Art Center pay tribute by screening one of his most central works on a film print provided to us by the Goethe Institut Boston. Special thanks to Brian L. Frye and Karin Oehlenschläger.

“Over more than four decades, Farocki produced an extraordinary body of work that, for someone who continuously compared things, situations, and images to one another, is paradoxically incomparable. In all he did, he kept it simple, clear, and grounded. In cinematic terms: at eye level. His legacy spans generations, genres, and geographies. And the abundance of ideas and perspectives in his work does not cease to inspire. It trickles, disseminates, perseveres.” – Hito Steyerl, e-flux

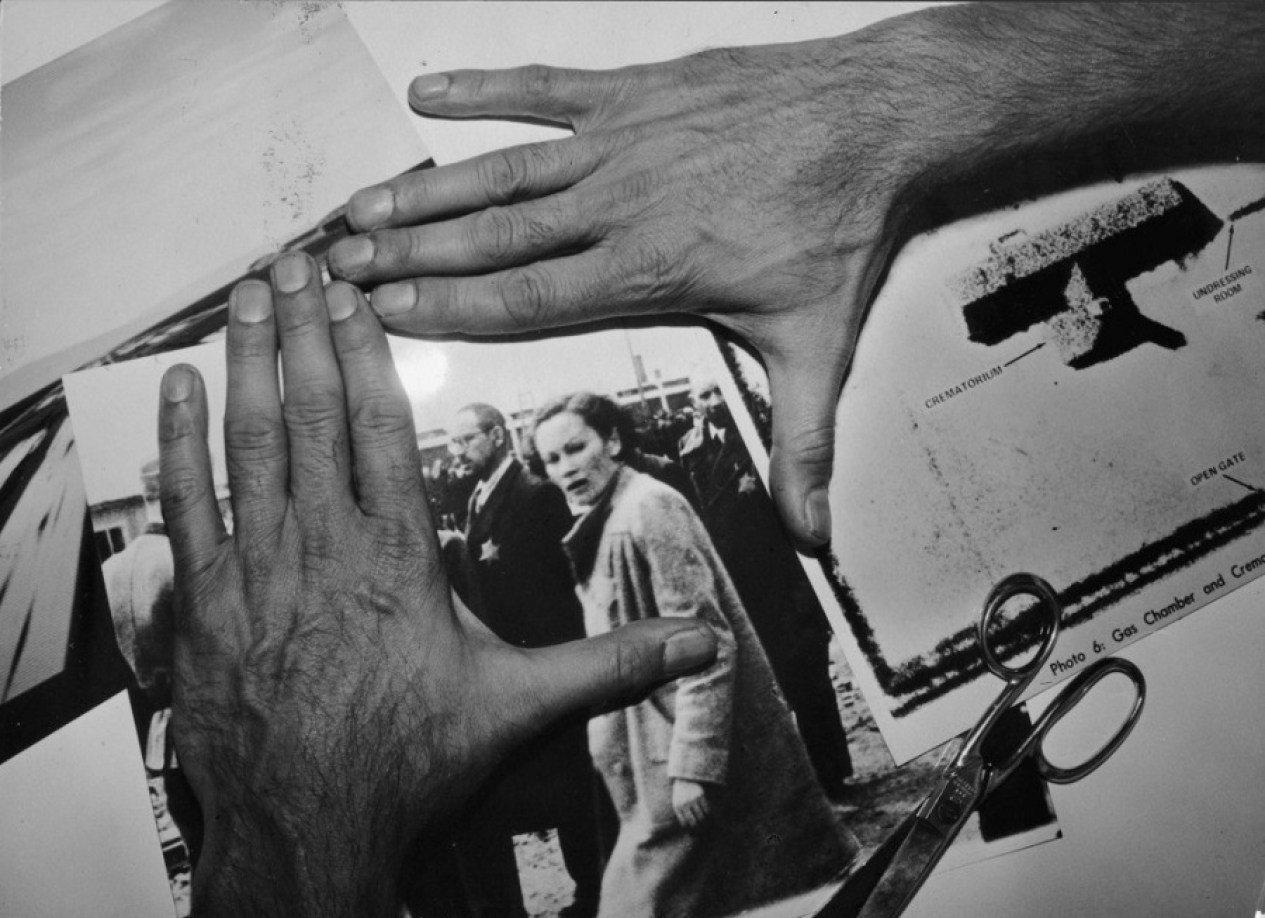

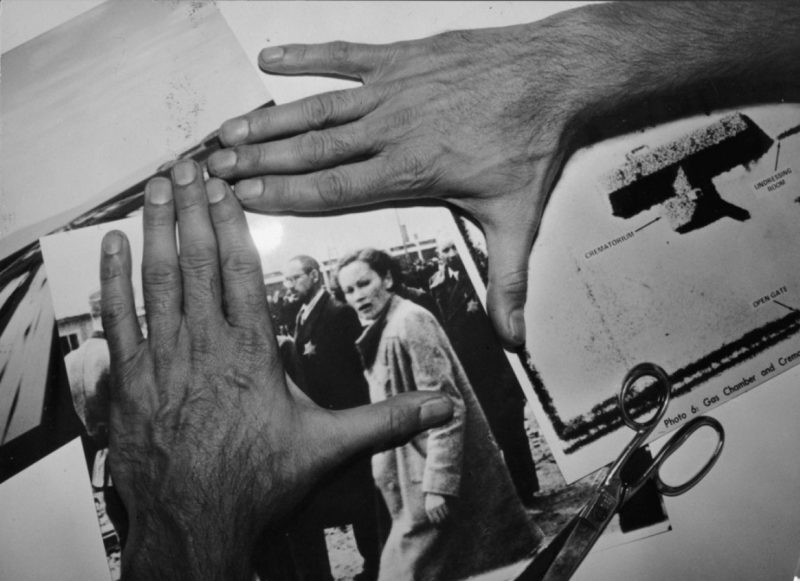

IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND THE INSCRIPTION OF WAR

Harun Farocki

74 min, 16mm, Germany, 1988

“After becoming every student film-club’s favorite meditation on the media and modern warfare in the age of smart bombs and Operation Desert Storm, Images of the World quickly advanced to something of a classic: the reference film, the anchoring point for seminars on Paul Virilio, on the essay-film as a hybrid documentary but politically subversive film genre, on the ‘limits of representation’ after Auschwitz and Schindler’s List, as well as – this needs to be rediscovered after September 11th – the definitive film about terrorism.” – Thomas Elsaesser, Senses of Cinema

“The vanishing point of Images of The World is the conceptual image of the ‘blind spot’ of the evaluators of aerial footage of the IG Farben industrial plant taken by the Americans in 1944. Commentaries and notes on the photographs show that it was only decades later that the CIA noticed what the Allies hadn’t wanted to see: that the Auschwitz concentration camp is depicted next to the industrial bombing target. (At one point during this later investigation, the image of an experimental wave pool – already visible at the beginning of the film – flashes across the screen, recognizably referring to the biding of the gaze: for one’s gaze and thoughts are not free when machines, in league with science and the military, dictate what is to be investigated. Farocki thereby puts his finger on the essence of media violence, a ‘terrorist aesthetic’ (Paul Virilio) of optic stimulation, which today appears on control panels as well as on television, with its admitted goal of making the observer into either an accomplice or a potential victim, as in times of war.” – Christa Blümlinger

“One must be just as wary of pictures as of words. There is no literature without linguistic criticism, without the author being critical of the existing language. It’s just the same with film. One need not look for new, as yet unseen images, but one must work with existing ones in such a way that they become new.”- Jörg Becker, TAZ, 1989

Assistant Director/Researcher: Michael Trabitzsch; Cinematographer: Ingo Kratisch; Animation Camera: Irina Hoppe; Editor: Rosa Mercedes with Harun Farocki; Negative Cut: Elke Granke; Sound: Klaus Klinger; Mixing: Gerhard Jensen-Nelson; Narrator: Ulrike Grote; Production: Harun Farocki Filmproduction, Berlin-West, with financial support from kuturellen Filmförderung NRW

—-

An e-mail Interview with Harun Farocki about Images of the World and the Inscription of War

by Dorothea Braemer

(Images of the World was screened at Squeaky Wheel in November 2003; it was the first screening organized by Dorothea Braemer, who had recently begun her tenure as Executive Director of Squeaky Wheel. Following the screening, Braemer interviewed Harun Farocki, in German and translated by herself, for The Squealer, low tech/high tech edition, 2003. We are republishing this essay on the occasion of screening this film again, 13 years later. SW)

The German filmmaker Harun Farocki has made close to 90 films, including three feature films, essay films and documentaries. His influential and thought-provoking work is not as much about events and people as it is about ideas and mechanisms in a larger cultural context. Images of the World and the Inscription of War (75 mins., 1988) is one of his most famous films. A meditation on vision and power Images of the World centers on a historical accident: In April 1944, U.S. bombers flying over Poland inadvertently photographed Auschwitz. Based on these and other images, the film creates striking, deeply meaningful connections between military reconnaissance and the state of the world. When Squeaky Wheel screened Images of the World in November 2003 I felt that the film resonated with new meaning and urgency. I was curious what Harun Farocki himself thought about his film now, and I emailed him with some questions which he graciously answered.

DB: At the beginning there is this wave-measuring machine. Ulrike Grote’s voice says: “When the sea surges against the land irregularly, not haphazardly … without fettering it and sets free the thoughts.” Is this an appeal for free (non-measurable) thinking? Or a preparation for what to expect – a film which argues in waves, non-linearly?

HF: Irregularly, not motionless: this was the intended structural design of the film. A challenge to identify or at least experience the rules. We did not film this canal of waves, this university research institute, in order to create analogies. In general, the production was guided by the principle to film in various locations where processes are simulated. The movement of water, by the way, cannot be studied in reduced scale – it has to be one to one. I like to look at the ocean, a suggestive image, which nonetheless frees ones thoughts. However, I did not want to show a real ocean. I preferred the model, where one imagines one.

DB: There is a brutality in photos whose meaning no one understands – neither the victims, nor the perpetrators, nor the photographer. I immediately had to think of the picture of Mohamed Atta, photographed at the airport security gate on 9/11. It is a miracle of technology that this photo exists – but a useless miracle, because it did not prevent anything. We are trying to control the world with surveillance technology – “a web of military reconnaissance systems to cope with all the events in the world” – you had written in a previous e-mail, comparing the world to a factory. But who is controlling this factory, if one does not understand the photographs anyways?

HF: Yes, at stake is the interpretive power of the image. For thousands of years the subjective component in historiography has been decreasing. History is recorded more and more by machines, by systems of inscription, rather than by actual people. In the case of Auschwitz this was particularly clear. During the Second World War postindustrial telecommunication was invented. The computers of the English decoded the codes of the Germans. Nonetheless, we needed living witnesses, we needed the prisoners Vrba and Weltzler, who were able to flee the concentration camp and provide living testimony to the existence of Auschwitz. One could also conclude that systems of reconnaissance cannot recognize anything new. Their registration is based on preconceived patterns. They cannot recognize something outside these patterns. In this case the new things were something horrible. But there is also hope.

DB: In the film you state that the word Enlightenment (Aufklaerung) also has a military meaning in German, as well as a meaning used in the police force. “Already then, work had to be created and this was done with war production and destruction.” I immediately had to think of Iraq and the many industries and people who make a lot of money with this war. Do you also see this parallel?

HF: Just like 70 years ago, the rich countries today face an enormous crisis in employment, and it is tempting to do something destructive. One can read about this in every business section of the newspapers, the hope that a war will stimulate the economy. But it doesn’t seem to work. It’s also questionable whether a victory over the Taliban or the regime of Saddam will create an impetus to modernize.

DB: The music, interrupted again and again (like waves, like thoughts, like a photo which one cannot clearly recognize?) – what was your motivation?

HF: I took famous classical pieces, from Bach and Beethoven, put the soundtracks into a sound degausser (to erase the sound), but put an opened pair of scissors on top. In this way, everything underneath the metal of the scissors was kept intact. During the sound mix I spontaneously said: now, the first piece, now stop. I had spent so much time with the montage and the images, that everything seemed too calculated to me. The film needed an improvised element.

DB: How about the French woman who is being made up?

HF: This woman is a model, who is being prepared for a shoot in a special way. The make-up artist is rubbing powder into her skin. I had filmed these images 15 years before and I remembered them again. Images of the World is about the connection between preservation and destruction. Here one sees how skin is made into something marble-like – for the sake of the image a living person is fossilized.

DB: At the beginning of the film the voice-over states: “One only finds what one is looking for.” In a drawing class a teacher advises his student to “first think, then draw, then think.” And at the end of the film resistance fighters manage to destroy a gas chamber, something that no one has been able to do before. Are you, as filmmaker, interested in showing or teaching? Or, put differently, do you want to change the world, or do you want to interpret it?

HF: Yes, it is important sometimes not to think, to be fully with the material and the process of working, in order to find something that pure reflection cannot reveal. A film should be logical, but there are several, even many kinds of logic. In this film I am trying to combine relatively few elements in different ways, creating permutations. And of course it is impossible to declare theorems, at best one can offer a certain look, certain connections. Like a novel, which also does not tell one how to live.

Dorothea Braemer is a filmmaker, educator and arts advocate. From 2003 to 2012 she was the Executive Director of Squeaky Wheel.