- This event has passed.

Jason Livingston, with Phoebe A. Cohen: In the Sun’s Absence

Opening Friday, March 22, 2024, 6–8 pm

Brief remarks by the artists at 7 pm

On view Tuesdays–Fridays, 12–5 pm and by appointment through June 14, 2024.

Squeaky Wheel is pleased to announce In the Sun’s Absence, a public art project and exhibition led by artist Jason Livingston in collaboration with Phoebe A. Cohen (Chair and Associate Professor of Geosciences, Williams College). Timed with the 2024 Solar Eclipse, and featuring haiku installed on public signage, sound art, video, print work, and sculptural projects. Livingston and Cohen state:

The upcoming eclipse affords a chance to consider the sun’s significance. For us, this means reckoning with fossils, fossil fuels, deep time, and deep futures which imagine worlds beyond the violence of capital, colony and climate crisis. The exhibit puts into motion these cosmic, molecular and human temporalities in a polyvocal constellation which crosses from gallery space to city streets, from wall to screen, from ink to sedimentary rock.

We love the materiality of objects. We think light is a material. The eclipse is material, as is our collective desire for multiple, just solarity. And we promise you, dear moon, we haven’t forgotten about you.

The project draws from Livingston’s public and environmental art practices and Cohen’s research into deep time. Livingston and Cohen have a shared interest in the Earth’s systems and the fact that the fossil fuels that run our economy are the preserved products of ancient photosynthesis. Through Livingston’s art works, audiences will reflect upon the foundational importance of our sun and its encompassing impact on the history of the Earth and humankind. This project was selected and has been generously supported by the Simons Foundation as part of their In the Path of Totality project.

Haiku in Buffalo

Along with the works in the exhibition, Cohen and Livingston presented workshops for Squeaky Wheel’s youth and adult education programs, where participants learned about the relationship of the sun to the creation of fossil fuels, and wrote haiku. Haiku were selected both as they are an accessible and popular form, but also as they traditionally feature seasons, cycles and nature.

Selected haiku can be seen installed on ten public billboards around Buffalo through April 9. See the map below or click here to see locations, participants, and their haiku.

You can listen to recordings of the haiku by participants here:

Documentation of the exhibition

Public programs

Wednesday, January 31, 6–8 pm

Eclipse Haiku workshop for youth and adults with Jason Livingston and Phoebe A. Cohen. Click here to learn more and register.

Friday, March 22, 6–8 pm

Opening of In the Sun’s Absence, with brief remarks by Livingston and Cohen at 7 pm. Catering by Southern Junction provided.

Friday, April 5, 12–2 pm

Tour of the exhibition with artist Jason Livingston and curator Ekrem Serdar

Wednesday, April 11, 2–4 pm

Open hours of the exhibition with artist Jason Livingston present

Tuesday, May 7, 7 pm, in-person and online

Screening | Rushes: Films and actions by Jason Livingston

Friday, June 12, 5–8 pm

Extended hours for exhibition closing

Jason Livingston

Ancient Sunshine, 10:26 min, 16mm film and iPhone video presented on digital video, sound on headphones, open captions, 2020

“A fossil cast in plastic, an artificial plateau, classic cars running on the fumes of the nation. Ancient Sunshine marks a path through fossil fuel extraction and climate defense in the American West. The film proposes solidarity against the violence by which “earth” becomes ‘resource.’

Utah Tar Sands Resistance has been fighting experimental mining in the Tavaputs Plateau for almost a decade, setting up camp every summer in sight of heavy equipment and construction crews. The film asks, how might the concept of horizontalism be applied to the physical horizon, its decimation, and to capital’s propensity for vertical extrication? Ancient Sunshine interweaves the endless remaking of the Western landscape with labor history, reflections on anarchist organization, and interspecies economies.

Ancient Sunshine consists of interviews with the Utah Tar Sands Resistance primary organizers and other Utah land protectors, and sets their voices in and against an industrialized landscape. The film presents an array of voices, drawing attention to the role of resistance and kinship during times of threat and extinction. Toward a poetic solidarity, toward a formal politics. – Jason Livingston

Jason Livingston

NOT ALL FOSSILS ARE GRAVES (positive) and NOT ALL FOSSILS ARE GRAVES (ghost), two pressure prints, 22 x 30”, 2024

NOT ALL FOSSILS ARE GRAVES is named after a remark Livingston made as Cohen explained to him that not all fossils are formed from the dead bodies of living things – some are instead the imprints and marks of still-living creatures. This began a conversation on the relationship between the indexical relationship between fossils and image making processes such as photography, and here, pressure printing.

The work also directly references what fossils – and by extension – fossil fuels are. Phoebe Cohen states: “…we often think of fossils as being associated with death. This framework that not all fossils are graves, to me, spoke of a sense of hope, and of, again, of a sort of resiliency. Also, in the sense of thinking about fossils as fossil fuels and that right now fossil fuels are leading us to our grave as a society, as a species. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Like fossil fuels, coal is not inherently bad. It is preserved ancient sunshine. It’s what we’re doing with it. It’s the choices that we’re making that are having a negative impact.”

The two prints – a positive and a ghost – were printed by Rachel Shelton at Mirabo Press and framed by Dennis Wisniewski at Buffalo Canvas.

Jason Livingston and Phoebe A. Cohen

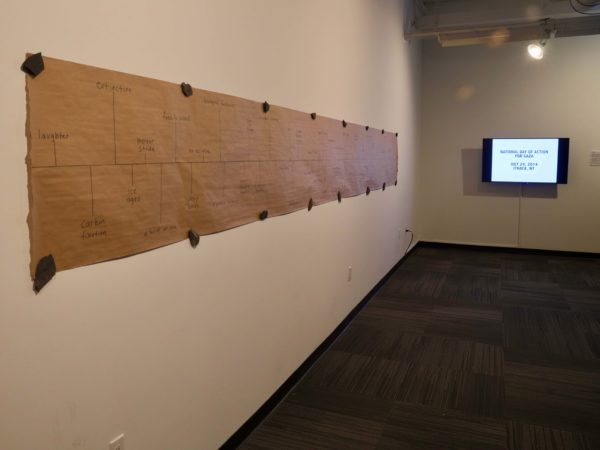

NO ONE NOON (paper), butcher paper, ink, 2024

NO ONE NOON (neon), neon sign, 2024

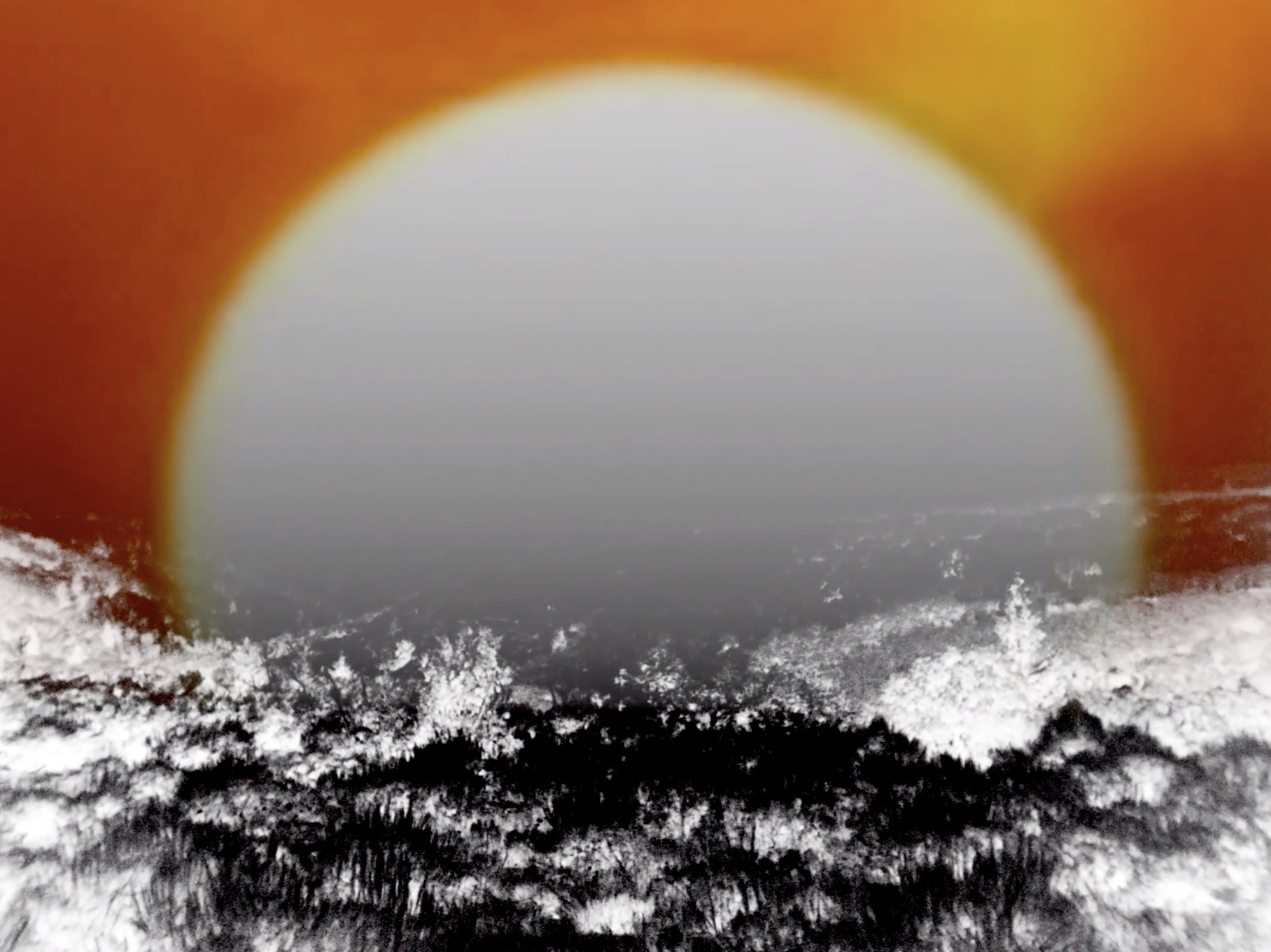

NO ONE NOON (video), looped, digital video, sound, 2024. Audio description: A low rumbling sound throughout.

The centerpiece of In the Sun’s Absence, the suite of works encompassing NO ONE NOON contemplate the nature of time. Emerging from an exercise that Cohen regularly assigns to her students to understand the vast nature of deep time, Livingston and Cohen plotted events across millenia on a long piece of butcher paper. Playfully, the timeline intertwines specific moments within the earth’s history such as the moment carbon is fixed with poetic, human ones, such as “gossip bonds.”

Underpinning the work is an essential discussion of the nature of time, and a debate between cyclical and linear interpretations of time. As Cohen stated: “We see an arrow moving forward and we think, what are we moving towards? ….evolution isn’t moving towards anything. It’s moving away from something. It never goes back. It does not have a direction in mind. Organisms respond to their environment in the moment and then the environment changes. They are not intending to go anywhere or do anything or be anything, except what they are in the moment. Timelines can be dangerous, and they have been used to promote a worldview that humans are the pinnacle of evolution, that we are the top of the mountain, as it were. That’s the danger of timelines. One of the things that we were interested in playing with was creating a view, a timeline where the moment that we are in right now was not legible, to basically pull the viewer away from that sense of progress or inevitability.”

This cyclical nature is iterated on in NO ONE NOON (video). The title of the work – repeated in Livingston’s haiku installed outside Tri-Main Center – is a palindrome.

Jason Livingston

7.24.14, 4:15 min, 16mm film presented on digital video, silent, 2014

7.24.14 documents protesters gathered in Ithaca, NY for the National Day of Action for Gaza on July 24, 2014. The action was called by over 100 social justice organizations around the country. That year, the Israeli military killed over 2000 Gazans through its “Operation Protective Edge”; the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs noted that 551 of those killed were children. Livingston’s silent film documents people gathering and hanging pieces of paper on a clothesline. On the paper are the names of child victims, the dates they were killed, and their ages, ranging from 5 months to 18 years old, with one referred to simply as “child.”

The film sharpens the intertwined nature of climate, capital, and colonialism that grounds In the Sun’s Absence. Speaking at the UN COP28 in late 2023 regarding the Israeli military’s current assault on Gaza, Gustavo Petro, the president of Colombia, noted: “I invite all of you to imagine a combination of facts — the projection of the climate crisis in five or ten years and the current genocide of the Palestinian people. Are these facts disconnected? Or can we look at there [Gaza] as a mirror of the immediate future? The unleashing of genocide and barbarism on the Palestinian people is what awaits the exodus of the peoples of the South unleashed by the climate crisis.”

Placed next to the millenia charting timeline of NO ONE NOON (paper), the clothesline of 7.24.14 brings much shorter spans into view, violently cut short by colonial power. With Ancient Sunshine, showcases Livingston’s long-standing work in charting social justice movements and tracing shared solidarities.

Jason Livingston

THE TOTALITY (pieces), mixed media, black light, 2024

THE TOTALITY (assembly), 5 hours, digital video, sound, 2024. Audio description: The majority of the video features ambient sounds from a city neighborhood: birds, cars on a street. During the total eclipse section, there are sounds of an oil pumpjack and a donkey braying.

THE TOTALITY (assembly), a five hour long video, features a 3 minute 45 second interpretation of the April 8, 2024 total solar eclipse daily at 3:18pm. The video directly takes on Livingston’s and Cohen’s focus on climate, colony, and capital, threading abstraction and representational elements as a durational experience.

During the majority of the film, it features contemplative 20 minute long shots of the sky, with slow-moving images floating across the screen of the infrastructures of oil extraction, border control, and war. At the time of the total eclipse, the work continues the wordplay present in the exhibition by intermixing images of oil pumps – often referred to as “nodding donkeys” – with footage of a donkey wearing a hand sewn blanket. Shot transitions foreground a graphical motif – seen on the donkey blanket – that is present on the billboards installed around Buffalo such as those used by the Geological Society of America, an interpretation of the geological timescale. The precise duration of the work places the work in the present as it looks backwards and to the future.

Next to the video work, on a shelf with a black light, THE TOTALITY (pieces) playfully looks towards the future. Small shapes featuring visual icons of the oil industry, the work is a speculative imagining of what a future fossil, unearthed by children, will look like.

The following conversation between Jason Livingston and Phoebe A. Cohen took place on February 16, 2024 over Zoom. It has been edited for clarity, and can also be read on our website.

Jason Livingston

You are quite active in public-facing science. You recently appeared in an episode of PBS Nova Ancient Earth, and you are currently producing a podcast called Jax and Phoebe Make a Planet! Can you say more about your passion for science, and sharing that passion with the public? Are stories helpful in communicating? What kind of stories do you want to tell, and how do you want to tell them?

Phoebe A. Cohen

That’s a big question. I have always loved sharing my enthusiasm for science and the natural world. And it’s been a part of my professional life since I graduated from college in one form or another. It comes from a variety of places. One is that I think the natural world is really fucking amazing and fascinating, and I think that I have had the privilege of being able to spend much of my life in deep study of our planet and its past. That is something that most people will never have an opportunity to do. It’s not necessarily because of a lack of interest.

As a paleontologist, people are always telling me, oh my god, I loved fossils as a kid, I loved dinosaurs as a kid, you know, I loved collecting rocks as a kid. And it’s always as a kid. A lot of my passion for communicating science is about sharing my enthusiasm, my knowledge, and my sense of awe and wonder for the natural world with adults. Not that sharing with kids isn’t important, but I feel like so many adults feel like they are disconnected from that part of themselves, or that they’re not allowed to have that sense of awe and wonder as grown-ups. That it’s something they had to leave behind as children.

I consider myself a storyteller. My science is a historical science. I will never know the truth about what happened 800 million years ago. My job is to take pieces of the past and weave them together in what I think is the most likely story given the evidence, given the data. Being a paleontologist, someone who works in deep time, requires a massive amount of imagination. I have to, in my mind and with my data, reconstruct a world that no one has ever seen, and no one will ever see. That requires imagination. It requires vision. It’s one of the reasons I love doing what I do. Storytelling is something that I’ve always loved doing; I’ve always loved reading stories and writing them when I was younger. It comes very naturally to me to want to communicate science as a story. That fits in well with this project, which is about bridging these artificial divides and schisms between the sciences and the humanities.

JL

I think sometimes people think that science is all about the truth or that science is only about certainty. Which isn’t the case. I’m wondering two things. One is, more broadly, if there’s something about stories that can allow for uncertainty, and then more specifically, if geological records can allow for that storytelling. As it turns out, there is a lot of uncertainty. There are a lot of things that simply aren’t known, like unconformities.

PC

Yeah, yeah. Missing time. The scientific method as taught in a seventh-grade science class is you have a hypothesis, you do an experiment, and you see whether the results of your experiment confirm your hypothesis or not, and if they don’t then you adjust your hypothesis. That works for a lot of biology and chemistry and physics, but it does not work for historical sciences like geology. It also doesn’t work for astronomy, which is also a historical science because you’re looking at light from stars or galaxies or supernova that is millions of years old. You can’t do an experiment on a black hole, just like you can’t do an experiment on a trilobite or a dinosaur.

And so we have to think about science differently. Like I said earlier, we will never know the truth. All we can do is do the best that we can, given the tools and information that we have, and that will change over time.

This is something that you and I have sort of butted heads with a little bit: this idea of, is there an objective truth? I think that I have some comfort with that uncertainty, up to a point. Because I still believe that like the natural world exists, that reality exists, and that there are observations that can be made about the natural world that are true. I knock my coffee off the desk and it will fall to the ground. There are rocks outside that we can date using geological and chemical techniques that are millions or billions of years old. Those things are true.

I think I have more comfort with uncertainty than other scientists do because of the nature of my discipline. And also because of my personality. But there’s a limit to that. I guess an empiricist at heart.

JL

There may be a productive tension between us but also between a lot of people in these kinds of collaborations. What I see is there’s the question of method and there’s the question of goal, and where it fits in the world, too. I think some of our differences have come out not so much about whether a rock can be dated and placed in time, because it can be. But where does that certainty fit into meaning making? Or in shared worlds? That may be where I place my focus in the arts and humanities.

When we began this project, we talked a lot about how the absence of the sun during a total eclipse affords an opportunity to think about the importance of the sun for all manner of things. Photosynthesis and life on the planet. The production of energy for all life forms, including the production of fossil fuels. The predicament we’re in because of burning fossil fuels. How we might imagine a transition to renewables and a more just distribution of resources. Now that we’re further along into the project, and the eclipse is a few weeks away, what are your thoughts on art’s role in imagining new worlds? Or maybe that’s too grand! Do you think art can play a role? What can we do to not fall into doom and gloom futurecasting? Feel free to be honest about art’s limitations. I see no reason to be overly rosy.

PC

That’s a really interesting question. I think of myself as a pragmatist when it comes to thinking about climate change and global change. Anthropogenic global induced change because it’s not just climate, right? We are inexorably altering the planet. Our actions will lead to the extinction of other species that otherwise would not have gone extinct in this time interval. That climate change is going to negatively impact our species and it’s going to disproportionately impact minoritized communities, the Global South. These things I believe to be true. I also am a deep believer in harm reduction. You can sort of use a harm reduction framework to think about climate change. My perspective is that anything we do is better than doing nothing. It will not only reduce harm on other species and ecosystems, but also on other people. If we can take actions now that will mitigate suffering, then I believe we have a moral and ethical responsibility to do so, even if we cannot reverse the impacts that we are enacting on the planet.

That’s my positionality in terms of thinking about where we are. I think being a doomer is a very privileged position. I also firmly believe in the Mariame Kaba quote, “hope is a discipline.” It requires work to be hopeful. She said that in the framework of abolition, but I think it holds just as true for thinking about environmental degradation and climate change and global change, global warming.

Anyway, art, right, art. I’m getting there, don’t worry!

My research is on 800-million-year-old tiny fossils. My research does not have a direct climate change focus. It doesn’t have modern-day relevance in the most specific sense of that term. So is what I do useless? No. Because what I’m doing in my research and my teaching is, I am giving my students a holistic and comprehensive view of how the Earth system works, and how it has changed over time, which is essential to understanding the situation we’re in now and how our impacts will affect the Earth system moving forward. It’s also just a way to share the Earth’s resilience, right?

Explaining that mass extinctions have happened in the past and that life and the earth have always recovered, I think, is a place of hope. So what does that mean about art? You could say, well, my work is not relevant, it doesn’t have inherent value because it’s not immediately addressing the societal problem of everybody right now. But that’s silly. It has value. And art has value too. I see my work and artistic work as quite similar in that way. Art has inherent value because it gives us a different way of seeing the world and seeing ourselves and seeing each other. Thinking about deep time and thinking about Earth’s history does a similar thing. It’s a way of twisting perspective and shifting someone out of their moment. That’s important for thinking about big problems. And big questions. I think it’s essential.

Are artists going to solve climate change? No. But no one person, no one discipline is going to solve climate change. It will require effort, work, creativity by people in all spectrums of society and all areas of inquiry. To say that it is only the responsibility of one group of people or another and that other people don’t have responsibility, I think, is wrong. It requires a shift in how we view ourselves as humans and art has a big role in that.

JL

I appreciate so much of what you’re saying right now. And I think it’s interesting to hear the quote you put forward from Kaba that “hope is a discipline” in the context of what we’re doing and in the context of our conversation, where we’ve been talking about the discipline of geology as scientific discipline. What if we think about discipline as a daily practice, of practicing something like hope or practicing something like imagination, working on those muscles as you would with yoga or baseball or drawing? We can elevate something that seems like it’s “merely” in the realm of imagination or sci-fi thinking or artistic experimentation to considering it as a discipline-

PC

-an area of inquiry, an area of work.

JL

An area of inquiry, yes, I think it’s productive to think about it that way. You’ve mentioned deep time, and I want to keep talking about that, as well as several key phrases that have come up for us. Some of them are drawn from paleontology and geology, or are scientific phrases, and a number of them are phrases that we’ve come up with or that we’ve created between us, like for example in the sun’s absence. Which has become an overarching title meant to unify or gather the disparate pieces in the constellation of works which will be sited in Buffalo leading up to and extending beyond the totality. No one noon, a palindrome. We’ve focused a lot on language. What are your thoughts about how we’re approaching language in our shared work? Perhaps we could begin by talking about the phrase “not all fossils are graves.” We were on a walk at Crystal Lake with Caroline Doherty in the Catskills, and it emerged in conversation. Why did that phrase land with you, and why did it stick with you?

PC

It’s a great question and I’ve thought about it since that moment. Language has played a big role in our collaboration, the language of my discipline and communicating that, and translating it to you. It’s been so cool and interesting to see the phrases from my discipline that have resonated with you. And, you know, one of the things that drew us together was the fact that you have this film called Ancient Sunshine. I have often talked about the fossils that I work on as essentially the remnants of ancient sunshine in the form of fixed organic carbon. I think that we found a lot of similarities in technical language and in metaphor around technical language, which has been exciting, I think, for both of us.

And yes, we were on this walk, and I was describing different kinds of fossils to you, and I was describing trace fossils in that moment, which are things like footprints or trackways or burrows that are evidence of the behavior of an organism as opposed to its actual physical body. It’s not like a shell or a bone. Your response to that was “not all fossils are graves.” There were a lot of layers to that for me. One is that we often think of fossils as being associated with death.

This framework that not all fossils are graves, to me, spoke of a sense of hope, and of, again, of a sort of resiliency. Also, in the sense of thinking about fossils as fossil fuels and that right now fossil fuels are leading us to our grave as a society, as a species. But it doesn’t have to be that way. Like fossil fuels, coal is not inherently bad. It is preserved ancient sunshine. It’s what we’re doing with it. It’s the choices that we’re making that are having a negative impact. There are two levels there. One is thinking about fossils in the sense of a bone, or a shell, or a trackway as being evidence of past life, right? Focusing on the life as opposed to the death of an animal or an organism, and then, on the other hand, thinking about the role of fossil fuels and ancient carbon in our current predicament. But can I flip the question around on you?

JL

Sure!

PC

So, you know, it immediately resonated with me and I think also with you, which was the inspiration for the amazing print that you did with Mirabo Press. I’m curious to hear from you, what about that phrase resonated from your perspective?

JL

I want to respond to one thing you mentioned, about how coal is not inherently bad, it’s what we’re doing with it. To tease out a bit of what you’re saying there about fossil fuels, which bring with them certain ideas or traces of ideas about fossils, or ancient life forms: I think this is strongly connected with what for some of us seems to be a death cult, an orientation toward a species-level flame-out or multispecies-level flame-out in the hands of capitalists.

There’s a carbon fixation, for those of us on the tree hugging side, where we might think, with this addiction or with this fixation, comes the death cult. If only it were so simple. If only it were just a matter of being released from the death grip of fossil fuels. But it’s a good deal more complicated than that. One of the things that art can do, I hope, is bring a productive ambiguity, a generative complexity, to these questions which can contribute to imagination. It’s hard to predict how that will go, of course! And it’s a humble contribution.

Around the moment that we shared together with Caroline on our walk, about not all fossils or graves, I think my first response was wonder, like being struck, like in kid mode. That little revelation of mind blown, what?! I didn’t realize that! At that level it was very powerful. As we talked about it and then as it sat with me, I thought about how there are these connections between fossils and images. The way that images index objects, as do fossils.

PC

Yes!

JL

The questions that sometimes the philosophically inclined get interested in. Is the thing the thing or is the thing not the thing? And that brought us deeper into the project-

PC

-right, and I’m interjecting because a couple of weeks before the retreat, I had been in the car with friends, and my friend Carolyn Clayton who’s an artist. I was describing this project to her in our collaboration, and she said, is a fossil a photograph? And that was another moment of stopping and thinking, having sort of an “oh shit” or “aha” moment. That definitely fed into “not all fossils are graves” and this idea of imprinting, indexing, which inspired the format that “not all fossils are graves” is taking in the exhibit.

One of the things that’s been so exciting for me in this project is stepping out a little bit, conversations that I’ve been able to have with not just you, but other artists in my life. I’ve stretched my conception of my work. It has allowed me to access my childlike sense of awe and wonder and curiosity in ways that aren’t always easy.

JL

I like that and I want to take that as an opportunity to remind you to bring your camera to Buffalo. I know that you are a long-time photographer. You have a fantastic eye. The Simons Foundation has encouraged us not to make anything or do much other than experience it, but maybe you’ll take some pictures?

PC

The camera will come.

JL

Okay! I feel like there’s further to go with language because at another point in the last half year of our conversations, we realized we were both interested in where deep time and metaphor come together. This led us to look at Stephen J. Gould’s writings about metaphor, about deep time, about geology and paleontology vis-a-vis pedagogy and storytelling, specifically time’s arrow and time’s cycle. These tools can be linguistic or visual or both, like the timelines and the timescales used in your field. We’ve decided to use the timeline, to riff on that. It’s become fundamental and is moving through our project in different iterations, for example on the billboards we’ve been creating. How do you or your colleagues use a timeline in a classroom? What are its benefits? But also, what are its limits? If you’ll allow me to use a pun here, what are its faults?

PC

Love your puns, so good! Timelines help us. They structure our thoughts. They also help us conceptualize processes. That are way beyond human conception. Things like the movement of tectonic plates, changes in global climate, the evolution of new species. Extinction can sometimes happen fast, but evolution happens pretty slow on human timescales. Many of those processes don’t make sense unless you can conceptualize the immensity of time over which they occur. You look out the window and you don’t see the North American plate moving away from the European plate, but they are. And again, that comes back to the imagination, right? I can look out the window and imagine that movement happening a micron at a time, but I can’t actually watch it happen during my lifetime.

I often use timelines in my courses to help students start to conceptualize for themselves the immensity of the age of the Earth, and to bridge the gap between human perception of time and geological time. Seeing a long roll of paper down a hallway, and realizing that all human history fits into the last half a centimeter is extremely helpful as a visualization to help students figure out what’s going on.

In a scientific sense or in terms of my research, timelines are necessary for us to figure out the order of events. We cannot pull apart cause and effect without knowing how old things are relative to each other. Or their absolute ages if we’re thinking about rates of change. Geochronology, the science of dating rocks is extremely important in my discipline and in many other disciplines because it allows us to get at causality and rate. Gould called this “tempo and mode”, the tempo of evolution, and then the mode type of evolution. Timelines that are calibrated are essential to that process as well. They serve a conceptual purpose, but they also serve a more immediate research function in terms of being critical to answering questions that we’re interested in as Earth historians.

JL

Hmm. At one point you and I discussed how a timeline can have an unfortunate effect; that the timeline may place the human being at the very end of linear time in the present moment, as if the human is the goal.

PC

Yes, the dangers of timelines. Yes.

JL

That’s something we have in view as a concern or as a question that we wanted to unpack in this project.

PC

Yes, that’s right. Thank you for prompting me, because the problem with timelines is that they imply directionality, and for humans, directionality is very much linked to a sense of progress. We see an arrow moving forward and we think, what are we moving towards? This is something else that I said at some point recently, which is that evolution isn’t moving towards anything. It’s moving away from something. It never goes back. It does not have a direction in mind. Organisms respond to their environment in the moment and then the environment changes. They are not intending to go anywhere or do anything or be anything, rather than what they are in the moment. Timelines can be dangerous, and they have been used to promote a worldview that humans are the pinnacle of evolution, that we are the top of the mountain, as it were. That’s the danger of timelines.

One of the things that we were interested in playing with was creating a view, a timeline where the moment that we are in right now was not legible, to basically pull the viewer away from that sense of progress or inevitability. I hope we’ve been effective in that. I think that’s a powerful change, again thinking about changing, twisting, altering someone’s view of themselves in the world, right? Both art and science can do this.

JL

I think of our timeline as very experimental. We had to sort through a philosophical conundrum and questions about method, to what extent nonlinearity is a useful tool for shaping time. You held the line when I was pushing for nonlinearity. We arrived at a good place, an engagement with a dynamic of time’s arrow and time’s cycle, to try to produce a timeline in which both are moving. We have the movement of an arrow and the movement of a cycle, with substitutions that are designed to hopefully bring people in. For example, rather than produce a timeline with a big bang at the beginning or all the way on the left, it begins with laughter. We have these recurring events, some of which are drawn very directly from geological sciences, phrases that a scientist might recognize, but also other phrases that are more poetic, more human oriented, a bit strange even, to move in and out of human consciousness, and not to place it at the end –

PC

– yes, but throughout. That was something that I struggled with at first when we were initially conceptualizing this because it was very hard for me to remove my attachment to my timeline. There is a timeline of the earth that exists in my head that I refer to continually. This is not that timeline. I was very excited about the idea of time cycles. When you started pushing on that there was a sense of discomfort that I had to get over, but then it transformed into enthusiasm and excitement. That’s been the case for both of us as part of this whole project, right? Pushing each other up against these moments of discomfort where we’re having to step outside of our disciplinary bins. I think we’re both used to doing that and good at it already, which is why this has worked. Even so, there have still been multiple moments where we’ve tried to do that.

JL

Very much so. For me it’s been a good exercise in discipline, asking myself how the tendencies in arts and humanities on what some people call geopoetics, or “fancy” words, can go so hard into imagination and ambiguity that certain tetherings can be compromised. It’s just to say that I think it’s dialogue that’s been at the center of our project. Without that, I don’t think we would have landed where we have. On the question of landing, I have one or two more questions. I thought we might take a moment to ground the project in Western New York.

PC

Yeah. Go Bills!

JL

Ha. Are there any rocks or geological features in Western New York or near Buffalo that interest you? What stories might local sedimentary rocks tell us? What kind of futures – if this makes sense – might we imagine from them? I’m asking you to tell us a bit about the specifics of rocks here, and I’m asking, if rocks tell us something about the past, can they tell us something about the future? Are stones fortune tellers?

PC

Most of Upstate New York is made up of rocks that were deposited at the bottom of an ocean in the Paleozoic era, from – I’m going to get the numbers wrong – 500 to 380 million years ago. At the time, the Taconic Mountains were very high, maybe as high as the Andes. They were formed by the compression of one small continent, pushed into the side of what is now North America. A big mountain range formed, and as it formed the crust on the back side of that mountain range flexed down and created a basin. Ocean water came in. That ocean was there for tens of millions of years. Sediments and life filled that ocean and those sediments and fossils of those living organisms fell down to the bottom of the ocean created thick layers of sediment. Tens of hundreds of millions of years later, the ocean is gone, the Taconics are now basically hills. Upstate New York mostly consists of these flat lying sedimentary rocks from that ancient ocean.

They are full of carbon. Some of them are very organic rich. Some of them are even what we call petroliferous, which means that if you hold it up to your nose it smells like gasoline because there’s so much organic matter in there. They’re also full of fossils. I happen to work on some of the microscopic fossils that are found just south of Buffalo. There are areas that are full of shells. Corals and clams and things like that. There’s a rich record of the life that lived in those oceans preserved in those rocks.

JL

Rocks tell us a lot about the past, but then there’s this other thing that we’re trying to think through, which is this future business.

PC

Can they predict the future? I think they can remind us about the inevitability of the future. They were once sediments at the bottom of an ocean. We are now covering the planet with ourselves and our cities and our domesticated animals. But we will also end up as sediment someday. We will be the past, just as those corals, preserved in rocks and Upstate New York, or once flourishing in that ocean and are now fossils. I think maybe they can be a reminder of the inevitability of time, and that when they were alive, that was the present moment. The idea that that ocean would disappear was unfathomable. If a coral could fathom-

JL

-if a coral could fathom!-

PC

-they were fish. Fish could fathom. Maybe. I don’t know. How’s that?

JL

Love it. One more. We decided early on that the center of our work would be these bi-weekly conversations. We also wanted very early on to bring in other voices to the project. That commitment has been like a loadstone, a way of navigating the process to allow for magnetic attractions and forces to shape outcomes. Partly this is an excitement about the unknown. How could haiku contributions generated in workshops change our direction?

The eclipse is a chance to wonder, to be in awe, to revel in our own senses. It’s also a chance to pause human overdrive, perhaps even pause human imagination in a curious way. Are we really in control? There’s these tensions and contradictions, then, in an eclipse, which I’ve been wanting to draw out. It’s a moment to ponder human insignificance. It’s also this moment to consider dumb human luck.

As I’ve learned from you, a total eclipse doesn’t stand outside of time. It has this weird temporality. Deep time but not eternal. Beyond human yet situated in time and space in such a way that we human beings are uniquely positioned to experience the phenomena in terms of how the earth and the sun and the moon line up. These contradictions are sublimely dynamic. So not only have I wanted to generate a totality poetics, if you will, to think with these dynamics and to think of these contradictions and the motion of it all, I wanted to bring in other voices, a chorus so that whatever language you and I are trading in, which is already impossibly metaphorical and metaphorically impossible, but a language beyond us, a language beyond you and me. Take this question as you will! We can talk about the phenomena itself or you can bug me about poetics. What about this craziness of how the eclipse is a very limited time offer from the cosmos from the position of the human?

PC

It’ll be around for a while, but eventually, yes, human evolution coincides with a time limited offer, part of Earth’s history where we have total eclipses because the moon is continually moving farther and farther away from the earth. We used to have more eclipses and eventually we’ll have fewer and then eventually we’ll have none, or no total ones.

How lucky are we? I mean, it didn’t have to be this way. I think maybe that’s another way of talking about decentering the human. As in the time scale, right? The Earth will go on and maybe other organisms will experience things that we have never been able to experience. But we get this. How cool is that?

JL

Before I learned from you about how an eclipse varies over time, that there is no such thing as a singular abstract eclipse outside of time, and that one day in the future the alignment of our planet with the sun and moon will eclipse, if you will, the phenomena of the eclipse, I think my focus was primarily on the way in which two objects that are spheres overlap with one another in the sky in such a way that the one blanks out the other and produces the phenomena, and I didn’t think about the other sphere that’s involved, which is the earth. It’s three bodies. In so far as it’s three bodies, it’s not so much a couple as a chorus. That’s why I’ve been wanting to bring in so many voices to the project beyond just you and me, to create a chorus, a polyvocality. We’re trying to produce something cosmic.

PC

Coming back to the beginning of the conversation about public engagement, what better way to engage the public than to engage the public? Like bringing people in, and giving them the opportunity to think about metaphor and time, is something that most people aren’t ever given the ability to do, and we can give people a glimpse of that, whether it be participating in one of our workshops or driving by one of the billboards. The potential for a moment of reflection, a moment of stepping outside of one’s human time scale and human framework.

I want to ask you one quick question. There have been multiple times over the course of this collaboration where I have been like, I don’t really know what that means, like poetics, for example. I know what poetry is. And so how has interacting with me been? Has it made you think differently about your own discipline and the limitations of it? What are you taking from this as you move forward in your own practice?

JL

It’s a great question. I think that working with you and working on these materials has invigorated my love and wonder for and about language in a way that I wouldn’t have predicted. When I look at my film practice, it’s full of language. If someone had asked me last summer “ What will you do next?” I might have said something like, “A film with no words.” But through this I’ve found so many rich meanings in scientific language, and in dialogue, which is often figurative out of necessity. I’m coming through on the other side with a wordless film on the horizon that I still may want to make, but I’m reminded of how important, and precious, words can be, especially when dealing with something like the mystery of stones and the rare transit of celestial bodies that will be on display.

Biographies

Jason Livingston is a media artist, filmmaker, and educator. His award-winning films have been widely exhibited at festivals and museums, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the International Film Festival Rotterdam, and Media City in Canada. He is currently researching histories of extractive cinema and abolitionist re-imaginings of our shared world as a Presidential Fellow in the Department of Media Study, University at Buffalo.

Phoebe A. Cohen is a paleontologist, geobiologist, teacher, and science communicator. Her research focuses on understanding the interactions between life and the earth system in deep time by integrating micropaleontological, geological, and biological lines of evidence. Phoebe is an Associate Professor at Williams College, where her research has been funded by the National Science Foundation and NASA. She is also the co-host of the forthcoming podcast Jax and Phoebe Make a Planet, and an advocate for inclusion and equity in the earth sciences and beyond.

About the In the Path of Totality initiative

This work is supported by the Simons Foundation and is part of its ‘In the Path of Totality’ initiative. For more information, visit inthepathoftotality.org .

This work is supported by the Simons Foundation and is part of its ‘In the Path of Totality’ initiative. For more information, visit inthepathoftotality.org .

The Simons Foundation’s mission is to advance the frontiers of research in mathematics and the basic sciences. Since its founding in 1994 by Jim and Marilyn Simons, the foundation has been a champion of basic science through grant funding, support for research and public engagement. We believe in asking big questions and providing sustained support to researchers working to unravel the mysteries of the universes. Through our work we make space for scientific discovery.

The Simons Foundation makes grants in four areas: Mathematics and Physical Sciences, Life Sciences, Autism and Neuroscience and Science, Society and Culture. Our Flatiron Institute was opened in 2016 and conducts scientific research in-house, supporting teams of top computational scientists. We recognize the value of collective effort and know that good science requires a diversity of perspectives. We actively promote large-scale collaboration through a pioneering grantmaking approach and are committed to the sharing of knowledge within the scientific community. We understand science is part of society and culture, and we actively provide opportunities for people to engage with science in ways that are relevant and meaningful to them.